近年来,那些成功被牛津、剑桥、哈佛、普林斯顿等名校录取的学生,几乎每个人都曾经参加过约翰·洛克写作竞赛,并且取得令人瞩目的成绩!

奖项设置

最高奖项

Grand Prize

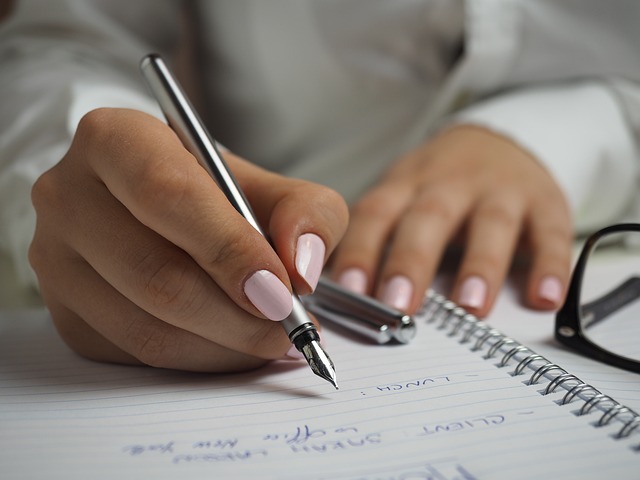

评委从所有参赛作品中选出一篇最佳作品。大奖获得者将获得John Locke青年荣誉奖学金。

学科奖

Winner(冠军)

Second Prize(二等奖)

Third Prize(三等奖)

*每个学科选出一篇最佳作品。获奖者的参赛作品将得到作者的许可后发表于官网。高年级组别每个主题及奖项仅1名。

入围奖

经组委会决定,未获得以上奖项,但是入围各科前20%的参赛者能获得Commendation/High Commendation奖项。

低年级组别设置一、二、三等奖各1名。

此外,奖励也十分丰厚。

每个类别的最佳作文都将获得一个奖项。每个学科组和低年级组的优胜者将获得价值2000美元的奖学金,可用于支付参加约翰-洛克学院的任何课程的费用,同时这些文章将在学院的网站上公布。

颁奖仪式将在牛津举行,获奖者将有机会与评委和约翰-洛克研究所的其他教员见面。

提交最佳论文的候选人将被授予约翰-洛克研究所青少年荣誉奖学金,该奖学金包括10,000美元的奖学金,可用于参加约翰-洛克的一个或多个暑期学校和/或间隔年课程。

写作高质量学术论文的关键是什么?

挑战性议题探讨:

选择更具挑战性和趣味性的议题,这可以吸引读者并展示独特的思考角度。

广泛探索和深入思考:

对选定的议题进行广泛的探索和深入的思考,通过收集和分析相关材料,构建自己的理论框架和观点。

掌握论文写作结构和论证能力:

熟悉基本的英文论文写作结构,并具备论证能力,包括引言、文献综述、方法、结果、讨论和结论等部分的合理组织和论证。

辩证思维和清晰论述:

在观点阐述中体现辩证思维,能够从多个角度思考问题,并清晰、完整地展开论述,确保语句通顺、逻辑清晰。

材料理解与运用:

理解并充分运用相关材料,包括学术文献、数据、案例等,以支撑自己的观点和论证。

合理论据和论证方法:

选择合适的论据和论证方法,确保论文的可信度和说服力,同时注重逻辑结构的完整性和连贯性。

写作风格和说服力:

注意写作风格的统一和论述的连贯性,同时注重论述的说服力,以吸引读者并使其信服。