距离2023年John Locke竞赛报名即将截止,John Locke论文写作竞赛被称为“文商社科赛事天花板”,想要报名的同学千万不要错过了!

约翰·洛克论文大赛由位于英国牛津大学的独立教育组织John Locke Institute与牛津、普林斯顿、布朗、白金汉大学等名校教授合作组织的学术项目,是爬藤选手中最热门的竞赛之一!

报名流程

第一步:登陆John Locke官网

官网地址:https://www.johnlockeinstitute.com/essay-competition

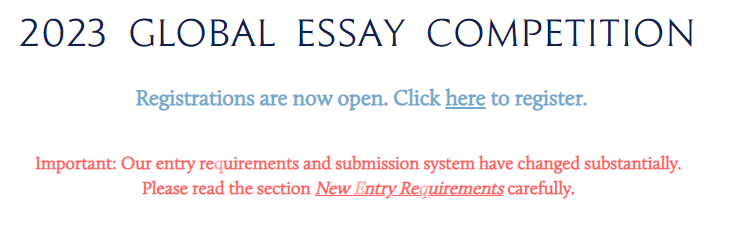

第二步:点击注册按钮

进入官网后,往下拉,看到有“Registrations are now open. Click here to register.”的提示语,点击“here”即可进入如下的注册页面。

第三步:邮箱注册

进入到注册页面后,需要填写一个有效的个人电子邮件地址来进行注册。确认无误后点击下方的【Login/Register】按钮,进入下一步。

系统会发送一个6位数的验证码邮件,登陆自己的邮箱,复制该验证码,在John Locke注册页面的输入框中粘贴验证码,接着点击【Log in/Register】按钮,进入个人信息填写页面。

第四步:填写个人信息并提交

个人信息部分需要填写的信息如下,某些信息栏右侧带有下拉箭头,点击该箭头可以选择对应内容:

名;姓;出生年月日;性别;联系电话的国际代码;联系电话;国籍;地址;国家;学校名称;学校地址;学校所在国家;你是如何知道John Locke等信息。

个人信息填写完成后,点击紫色框内的“Create Profile”,就会跳转到你的个人信息页面,代表注册报名已经完成 。

选题分析

2023年的John Locke论文竞赛即将到来,根据入围人数以及参赛人数的情况来看,经济、历史和政治是三大热门参赛领域之一。

在政治经济领域,参与人数一直保持在竞赛总参赛人数的1/4左右,是整个竞赛中最重要的核心之一。竞争压力极大,因为近1700人的参赛作品之中,要脱颖而出非常不容易。

历史领域一直保持相对稳定的参赛人数,但是仍然是竞赛中的中坚力量,始终位于竞赛第二的位置。虽然其参赛人数没有太大的变化,但竞争水平并不容小觑。

而政治领域在2022年的参赛人数方面增长迅速,预计是2021年的近2.6倍。这可能与近期国际社会频繁发生战争、贸易等问题有关,因此很多学生选择这个领域,选题难度也因此增加了不少。

心理学和法学这两个领域的参赛人数也有很大的增长,是2021年的两倍以上。这可能是因为这两个学科更加贴近学生的日常生活,更具有实用性,因此越来越多的人选择这个方向进行研究。

哲学领域和低年级组的参赛人数相对较少,增长也比较缓慢。这可能是因为这两个领域学科比较深奥,对于年龄较小的学生来说比较难以理解和掌握。虽然竞争压力相对较小,但想要取得好的成绩仍然不是一件容易的事。

扫码免费领取John Locke往年优秀作品

咨询报名注意事项+预约试听体验课

预约最新真题讲座、课程详情可添加下方顾问老师咨询